Summer Reads 2022 - Bridget

June 25, 2022

This is my first ever Summer Reads post! I became a bookseller with Librairie D+Q at the very start of Spring 2022, and it has been wonderful to see the return of warmer weather, greener greens and the sublime surprise that always accompanies the thawing of a Montreal Winter. During these past few months, more and more people have been stopping by the store (in fewer and fewer insulating layers), and every day brings a great conversation about what you’ve been reading, what I’ve been reading, and what the two of us ought to read next. Here are just a few of the books I’ve been rhapsodizing about lately; all of which would go along very well with a picnic blanket in a shady spot at your favourite parc, a chair on a rickety wrought iron balcony, a wooden patio erected to block a lane of traffic on Saint-Laurent, a synthetic glacier in the Animals of The Subantarctic Islands enclosure at the Biodome, or on the podium at the Olympic stadium where Nadia Comăneci scored the first perfect ten in gymnastics in 1976. I consider all of these equally iconic Montreal sites and all equally appropriate places to start a good book.

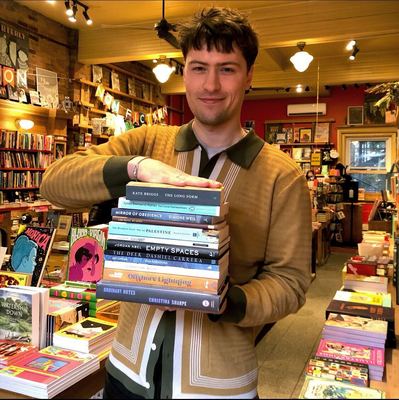

Rave

Rave

Jessica Campbell

A queer coming-of-age story, complete with secret cigarettes, gross gym teachers, and a lot of churchIt’s the early 2000s. Lauren is fifteen, soft-spoken, and...

More InfoRave is a new title from our publisher and a completely eviscerating and tender account of queer teenage girlhood; 'eviscerating' and 'tender' also being the best way I can think of to describe the experience of actually being a teen girl. Campbell does a terrific job of making the rites of passage that might seem universal feel as specific and transcendent as those actual experience of firsts really were: first kisses, first cigarettes, first encounters with the leering violence of gross old guys, first heartbreaks. We meet Lauren, Campbell’s protagonist, at one of the most consequential and confusing times in her life. She’s having a crisis of faith around the hyper conservative evangelical church she’s been raised in, and feels intensely drawn to Mariah, a cool Wiccan girl at her school. Rave is funny, in that way that the person you shared an intense friendship with in high school, borne from those messy first attempts at intimacy and chosen family, could make you laugh harder than any other person could. But it’s also delightfully angsty, precise in its skewering of a culture of hypocrisy around virtue and purity, and the trauma of trying to come of age under those conditions.

I Never Promised You A Rose Garden

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden

Joanne Greenberg

The multimillion-copy bestselling modern classic of autobiographical fiction about a young woman’s struggle with mental health, featuring a new foreword by Esmé Weijun Wang, the...

More InfoI Never Promised You a Rose Garden is a work of autofiction by Joanne Greenberg, first published in 1964, and reissued with a foreward by Esmé Weijun Wang in May 2022. I’d recommend Rose Garden to anyone who enjoyed Wang’s brilliant 2019 book The Collected Schizophrenias or anyone contemplating the agonies and ecstasies of another “sad girl summer”. In the midst of a representational crisis in how we think about and create a visual culture of mental illness in women and girls, Greenberg offers a prescient intervention from almost 60 years in the past. Her portrait of Deborah Blau, a 16 year old girl with schizophrenia, is a story about institutionalization and the compounding social, neurochemical and historical forces that prevail upon what it means to be considered unwell. We learn about the ways that Deborah’s early childhood was haunted by subtle and overt displays of Antisemitic hatred, from her Gentile neighbours, from a riding instructor at summer camp, and from the inherent trauma of growing up as a Jewish girl during and following the Holocaust. These details signal the ways illness and disability are refracted through lenses of racialization and additional markers of otherness. Some aspects of Deborah’s story and, we might imagine, Greenberg’s as well, feel specifically midcentury–more Bell Jar than #BellLet’sTalk–but others feel very resonant to the forces of shame and normativity that still attach themselves to our understandings of neurodivergence. Rose Garden is not only a narrative of Deborah’s traumas, but of her treatment, in all its setbacks, disappointments and imperfections. Is it not in any way a novel of cloying optimism or of romantic languid suffering, but a story of the lifelong negotiations that come with mental illness. Deborah’s psychotherapist, named for Greenberg’s real life practitioner, Dr. Fried, tells her, “I never promised you a rose garden. I never promised you perfect justice [...] and I never promised you peace or happiness. My help is so that you can be free to fight for all of those things. The only reality I offer is challenge, and being well is being free to accept it or not at whatever level you are capable. I never promise lies, and the rose garden world of perfection is a lie... and a bore, too!”

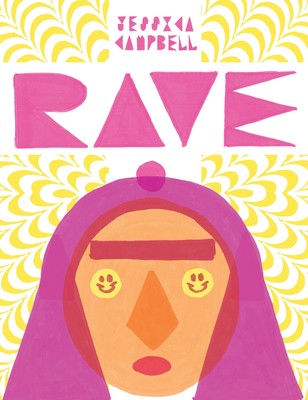

Just By Looking At Him

Just by Looking at Him

Ryan O'Connell

From the star of Peacock’s Queer as Folk and the Netflix series Special comes a darkly witty and touching novel following a gay TV...

More InfoJust By Looking At Him is the first novel by comedian, showrunner and performer Ryan O’Connell. I was a big fan of O’Connell’s massively underrated Netflix show Special, and look forward to seeing him in the newest iteration of Queer as Folk. Just By Looking at Him is bawdy and funny and a perfect read to celebrate Pride month with, which, due to the placement of Montreal Pride’s festival in Mid August, actually lasts 3 months as far as I’m concerned. The novel takes on some of the same questions that Special foregrounds, questions of desirability, disability and how those intersect with issues of access and privilege in queer communities. Elliott, the protagonist of Looking at Him, is a TV writer and a gay man with cerebral palsy. But just as things appear to be going right for him, gaining success in his career and a wonderful boyfriend, Elliott must also come to terms with a worsening alcohol dependency, the compulsion to cheat on said wonderful boyfriend with sex workers, and all the immense obstacles that come with navigating an ableist world. The decisions Elliott makes are messy and frustrating and deeply understandable. We watch him grow and evolve, and we watch him fail to grow and evolve. Still, he has the capacity to change, even when it comes to those things that we tend to be the most immoveable on, like the long term value of Kyle Richards to The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills franchise–“not the most compelling housewife but an excellent producer and provides access to her sisters Kathy Hilton and Kim Richards, who are National Treasures”. The chapters of Looking at Him are snappy and short and totally enthralling. For a taste of O’Connell’s comic sensibilities, I would also recommend checking out his recent appearance on the Las Culturistas podcast where he talks at length about RHOBH and some of the writing process behind Just By Looking At Him.

A Tiny Upward Shove

A Tiny Upward Shove

Melissa Chadburn

“Wild and ambitious . . . [with] something ablaze at its core. It burns.” —The New York Times Book ReviewA Tiny Upward Shove is...

More InfoA Tiny Upward Shove is perhaps the book on this list I’ve spoken the most about. Customers who’ve taken up this recommendation have returned to the store in a matter of days with all kinds of similarly buzzing thoughts on this excellent, harrowing and heartbreaking debut novel. The author, Melissa Chadburn, does something so skillful and surprising with a topic that almost always resists responsible representation. The novel is the story of Marina Salles, a fictionalized young woman who, before we’ve even had the chance to met her, has already become the victim of the real life serial killer Robert Pickton, a pig farmer and butcher who targeted unhoused women, drug users and sex workers in Vancouver’s East Side during the mid 90s. We meet Marina in the instant of her brutal murder, a moment that appears to exceed the unitdy seams of history and send the knotted threads of violence, colonialism, inheritance, curses and revenge unspooling wildly in every direction. Marina, a young Black-Filipina queer girl, becomes a vessel for, or rather a collaborator with, a mythic ghost-creature from Filipino folklore, the Aswang. The being has already inhabited many of Marina’s ancestors, and we receive their histories, not as corollaries or tangents, but as pasts that won’t be past, as a continuous set of ruptures that upend the linear passage of time, in the way that trauma tends to do. You’re brought along with Marina’s foremothers to the rural Philippines during early Spanish Colonial Rule, to the diner where her Lola first met “pakshet” grandfather–“pakshet” being a Tagalog portmanteaux of “fuck” and “shit”. The book’s prose is beautiful, expansive and profane. It employs critical fabulation, coined by the brilliant Saidiya Hartman, to merge fiction and nonfiction, to imbue the abject banality of gendered violence with mythological significance, without turning the real suffering of murdered women into spectacle. Much of the story seems to be narrated from inside the bodies of the women that populate it. We’re positioned claustrophobically close to the Aswang and to Marina, who are neither discrete nor entirely merged entities. We share in all her righteous anger and the urgency of her unfinished business. A Tiny Upward Shove serves as a gesture of radical compassion, but also as a reflection on the contradictions and fraughtness of narrativizing trauma on behalf of those who cannot.

Tacky

Tacky

Rax King

An irreverent and charming collection of deeply personal essays about the joys of low pop culture and bad taste, exploring coming of age in...

More InfoTacky is a brilliant collection of essays singing the praises of “the worst culture has to offer”. Author Rax King touches on everything from Diners Drive-Ins and Dives, to The Jersey Shore, to Degrassi The Next Generation, to Sexting. What results is loving a pastiche of early aughts kitsch that completely upends the construct of a guilty pleasure. Part sociological analysis, part memoir, King reflects on big unwieldy things like girlhood friendships, intimate partner violence and the death of a parent, alongside the artifacts that best allow us to access Our Big Feelings, and are, perhaps for precisely this reason, among our most scorned and misunderstood cultural objects. Before the release of Tacky, I was a fan of the funny and deeply affecting way King writes on both her twitter and on her Patreon, so getting to hear her read her voice in longform was such a lovely treat.

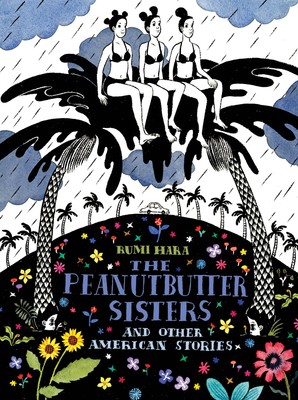

The Peanutbutter Sisters

The Peanutbutter Sisters and Other American Stories

Rumi Hara

An immigrant weaves a new, surreal Americana, complete with bubblegum fights and bomb queens.Rarely does a new talent arrive in the medium as unmistakably...

More InfoThe Peanutbutter Sisters and Other American Stories is the latest graphic novel by Rumi Hara, the author of the wonderful Nori. The short stories that make up the collection are funny, surreal, obscene and tender. They’re one part science, fiction, one part magical realism, one part something else all together (Leave your suggestions for what that something-else-altogether might be down below.) Dystopia and Utopia are inexorably enmeshed in Hara’s stories, as they are most likely to be beyond the page. You and your sisters hitch a ride into the heart of Manhattan on the back of a whale, but find that the ocean has dwindling few sea creature taxicabs for your return trip. You get your big break as a sports journalist and commentator for the 23rd Annual Intergalactic Race of Living Things and recall that special bittersweet camaraderie that robots can never quite replicate. I read Peanutbutter Sisters in a single sitting, enjoying every one of Hara’s totally unique and fully realized little worlds. Her art style is totally her own and incredibly beautiful, blending delicate watercolors with thick, dark, precise linework. Between each story there is a full-colour centrefold of sorts, depicting the eponymous Peanutbutter Sisters being semi-feral and delightful, hooting and hollering and hanging gleefully off the side of a semi truck. These images alone are totally engrossing but I think the whole collection takes you into its maw and doesn’t let go (in a good way, like a warm comfortable animal’s maw that it’d be nice to hang out inside for the afternoon).

The Breaks

The Breaks

Julietta Singh

A profound meditation on race, inheritance, and queer mothering at the end of the world. SEMINARY CO-OP'S BEST BOOKS OF 2021 In a letter...

More InfoThe Breaks is a totally singular work by Julietta Singh. The book takes the form of an extended letter to her daughter and includes insights into “mothering at the end of the world” that leave you positively winded. Singh offers intensely personal reflections on the racism of the overwhelmingly white academy, climate grief and queer parenting, and also provides her daughter with a kind of life-syllabus, including works like Robin Wall Kimmer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, as a form of citational care. The book was an excellent and evocative read and made me reflect on how often our culture instrumentalizes the figure of the child and calls it an act of love. Singh’s project goes completely counter to this. Her daughter is not a metaphor for futurity or a bundle of symbols and adult anxieties, but a whole person, as well as the addressee of a brilliant and thoughtful extended essay. Lauren Berlant, the author of Cruel Optimism brilliantly aligns The Breaks with James Baldwin’s A Letter To My Nephew. Singh, like Baldwin before her, does not uncritically replicate the conventions of inheritance or the automatic authority of an adult-child dynamic. She renders ambivalence and disorientation just as beautifully as she renders constancy and hope. Mothers, like children, are often treated as vessels for well-intentioned political messaging that reduces them to simile, evacuating them of agency or meaningful complexity: “The earth is our mother and so we must save her” and so on. Singh searches for new ways of representing our obligations to one another. “Whose bodies are ours to protect?” She asks. “Whose children are we free to discard? Who can flee to safety, and who gets left in the lines of fire? Whose worlds have been destroyed, and whose are soon to be? Does it make sense to distinguish between a child’s body and the body of the earth?”

Lote

LOTE

Shola von Reinhold

"LOTE recruits literary innovation into the project of examining social marginalisation, queerness, class, Black Modernisms and archival absences. A critically important and hugely original...

More InfoLote by Shola von Reinhold is a book I’ve been eagerly awaiting for almost two years! The book was first released in the UK in 2020, and I was lucky enough to have a brilliant friend and curator who got her hands on a copy of the book long before it was released in North America. Now that it’s finally widely available, and in a gorgeous purpley-pink reprint from Metonymy Press, I’m delighted to get to share it with you! My friend Faith, director of the 2022 Atwater Poetry Project, sold me instantly on the novel’s “temporally topsy turvy archival mystery about queer Black Modernist ancestors and a battle between the dazzle of cultural ornament and dullness”. The novel, like a Tiny Upward Shove, is a work of critical fabulation, of speculation and silences and secrets tunnels into a past that runs parallel to the present. von Reinhold is ambitious and virtuosic in her prose, and what results is a book totally unlike anything you’ve read of late. At the time of this post, I haven’t yet finished Lote, but I’m so excited to see more and more people delve into it, and already eager to see what von Reinhold does next!

Take The Long Way Home

Take the Long Way Home

A classic road trip memoir about love, family, and Canadian wildlifeIn 2019, artist Jon Claytor said good-bye to the Maritimes and hit the road....

More InfoTake the Long Way Home is both a phenomenal new graphic memoir from Jon Claytor and a phenomenal Supertramp song, making it all the more exciting for people with my specific (and unimpeachable) tastes. Take the Long Way Home is a classic road trip story, but also a narrative of recovery and a kind of retrospective on the people and places and animals that pass in and out of our lives. Ephemeral and effecting, Claytor’s beautiful linework feels like watching cities and forests, lives led and lives unled, flicker past you in the window of a moving car. When we meet Jon, he is not-quite two years sober, reeling from a breakup and the sudden disclosure of a family secret. His 8-week drive from the Maritimes to an artist’s residency in Prince Rupert is full of both immense loneliness and heartening reunions, as he reconnects with old friends, exes, and sobriety communities scattered across the country. The friendships he describes feel so real and familiar, so resonant to my own relationships that I found myself feeling heartsick over the people I still see every day, in anticipation of all the ways that we might someday grow apart. In a way I can’t yet articulate, I also think Claytor has something very resonant to say about the function and semiotics of cars themselves. Driving is such a deeply weird and unnatural risk, one that many of us take every day. Risky not just because of possible inclement weather or the relative brittleness of aluminum when traveling 100 km/h, but because of the enormous trust that driving requires we place in one another in order to override any reasonable terror. Being in a car requires a degree of magical thinking, to believe that everyone else on the road is trying their best to drive safely and responsibly, to know that you and they are still fallible in spite of this, and to not think too deeply about the precarity of this logic, lest you freak out behind the wheel. Driving is also something to be ambivalent about on a macro scale: the emissions, the disappearance of walkable cities, the little woodland creatures that might tragically wander across a highway that used to be their warren. It’s scary and strange and sometimes the only way to get where we need to be going. This kind of makes it a perfect literary vehicle (ha) for the moment of transition we join Claytor in, when we must both reckon with our disappointments and regrets but still focus on safely arriving in our future.