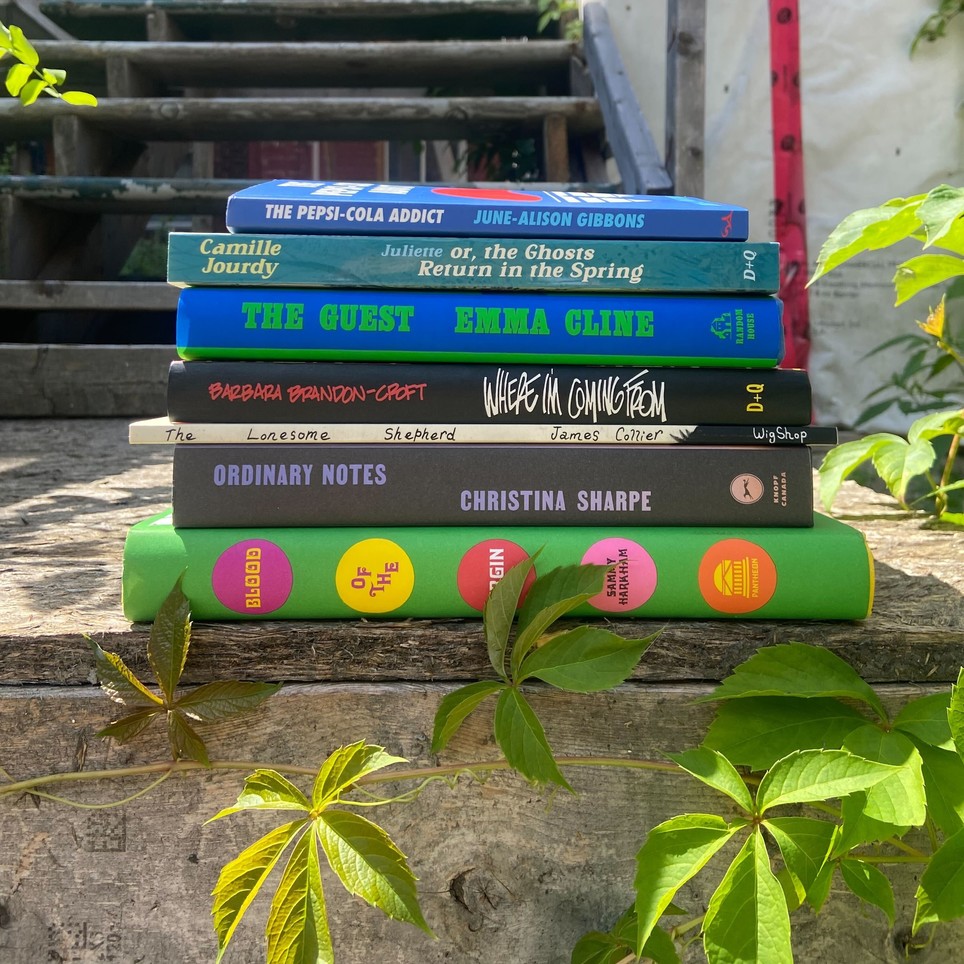

Summer Reads 2023 - Bridget

August 6, 2023

Well, here we are! Halfway through another Montreal Summer! The Summer that is meant to be our prize for being good boys all winter long, for hardly ever complaining, and zipping into our snowsuits all on our own. It's a (ruefully) short span of weeks that carry a lot of expectations, a lot of anticipation and a lot of opportunities to sit on a scraggly patch of grass and sip a hard seltzer with the Outside Friends you missed during our collective hibernation. This isn't to say that Summer is a disappointing reward for a winter well-spent. It's an excellent one, one that I always agonize over spending correctly. Summer summons a particularly potent strain of melancholy that I believe Hippocrates described as "FOMO". Learning to keep this despondence at bay, means habits that are either 1) meaningful or 2) meaningfully fun. One of the few activities that consistently results in the feeling of a day-well-spent is sitting in the semi-shade and reading a good book. Here are some of those good books! Enjoy your prize. You earned it.

Ordinary Notes

Christina Sharpe

One of The Millions’ “Most Anticipated Books of 2023One of The New York Times’ “19 Works of Nonfiction to Read This Spring”A dazzlingly inventive,...

More InfoOrdinary Notes is a book thats form confounds description. It’s a series of missives, of ruminations, of analyses, of protest and of memoir, from one of our moment’s most crucial thinkers. I wrote about my anticipation for this title in my 2022 end of year roundup, and it wound up far exceeding my expectations. Sharpe’s 2016 book, In The Wake: On Blackness and Being, is a vital and paradigm-shifting academic text, published by Duke University Press, and read widely both in and beyond the field of Black Studies.

In the Wake

Christina Sharpe

In this original and trenchant work, Christina Sharpe interrogates literary, visual, cinematic, and quotidian representations of Black life that comprise what she calls the...

More InfoSharpe’s writing has always contained traces of the lyrical, alongside the elucidative and precise, but in Ordinary Notes her voice is especially expansive and virtuosic. She moves seamlessly through different registers: candid personal history, trenchant cultural criticism, and poignant meditations on memory, memorial, Blackness, and beauty. It’s the perfect book to keep on your person all summer long, to thumb through whenever the moment presents itself, letting every fragment bowl you over—over and over again.

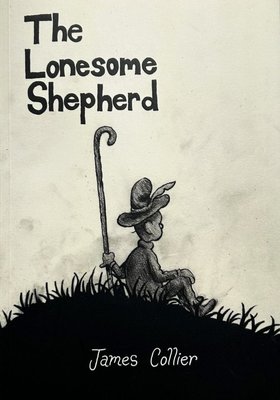

The Lonesome Shepherd

James Collier

A shepherd without sheep wanders the hills. An injury leaves him more lost than before. Our hero’s path intersects with other wanderers around him,...

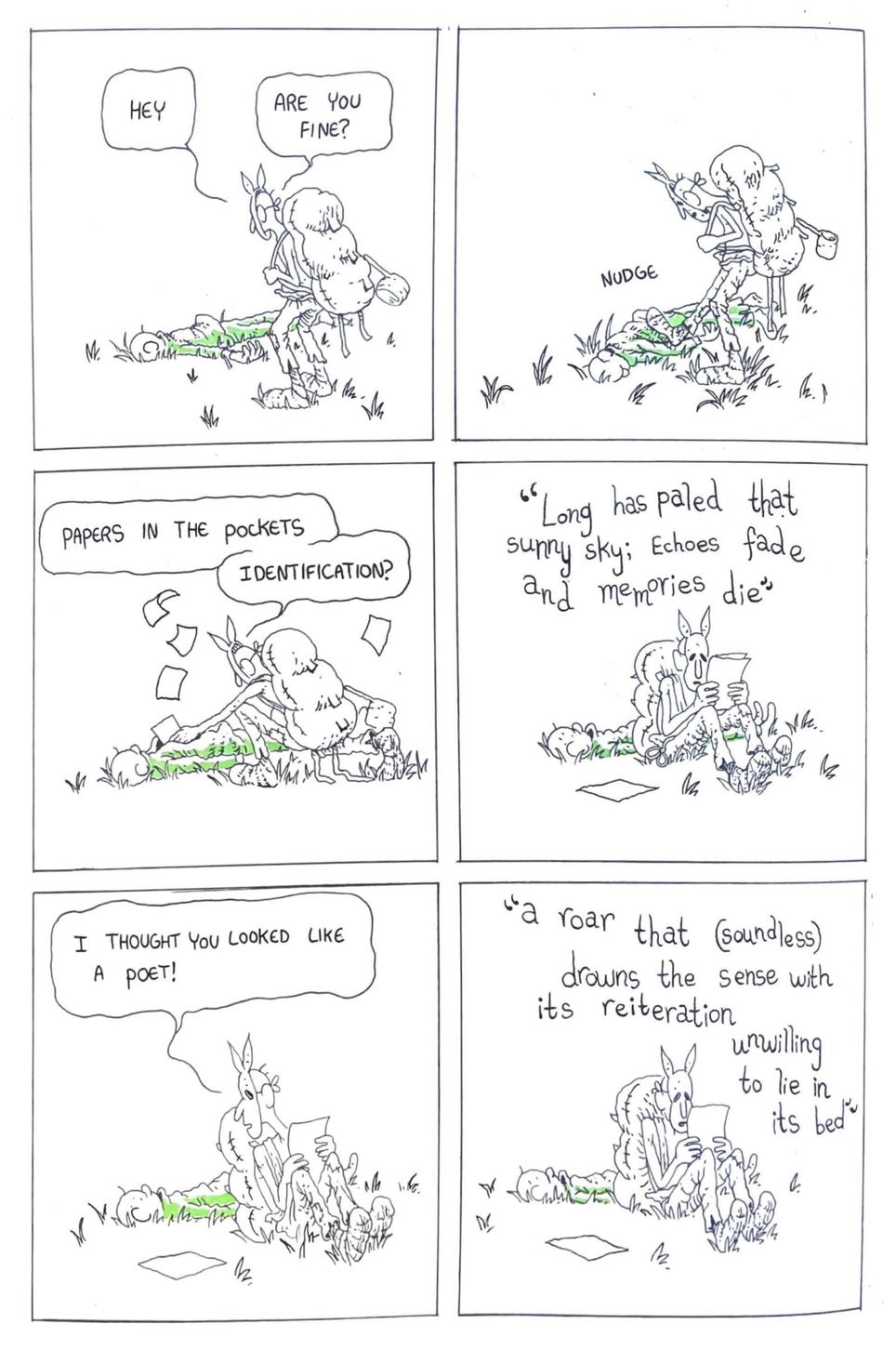

More InfoThe Lonesome Shepherd is a brilliant new comic from local cartoonist James Collier. Funny, profound and quietly heartrending. It's a sort of storybook of longing, deferred ambition, and all the small, strange kindnesses that make disappointment survivable. The Would-Be-Shepherd at the centre of the book wanders a mountainous wilderness, wisting after a flock of his own, certain that he will, by hook or by crook, fulfill his dream of becoming a Shepherd. It’s an ambition that has persisted so long that its absence has become load-bearing to the not-shepherd’s life. Despondence, like all things felt in excess, is always a little poetic and a little ridiculous. See below for a glimpse of the beautiful art style and a characteristic humour of The Lonesome Shepherd.

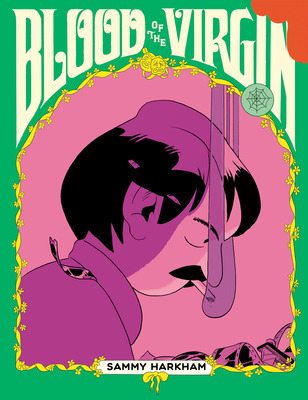

Blood of the Virgin

Sammy Harkham

“A story about storytelling...Conjures up the grindhouse movie-making scene in 1970s Los Angeles and tracks an ambitious young man’s flailing attempts to build a...

More InfoBlood of The Virgin is a labour of love for artist Sammy Harkham, a graphic novel that took him over a decade to write, and carries those years of intention with astounding grace. It’s a story that is exceedingly specific, an Jewish-Iraqi immigrant filmmaker trying to establish himself in the grindcore scene of 1970s Los Angeles, and therefore able to speak to near-universal experiences of belonging, exclusion, sexuality, ambition, fear, family and art-making. Harkman’s drawings are beautifully evocative of a mood and setting that echoes Boogie Nights or, more recently, the television series The Minx. It’s an era of grimey glamour and camera lenses smudged with vaseline, of cynicism and utopia commingling on the edge of a suburban swimming pool in the San Fernando valley. Its visuals are both historically specific and timeless, with scenes of working class domestic life rendered alongside the heightened visual language exploitation cinema.

The Guest

Emma Cline

A young woman pretends to be someone she isn’t in this “spellbinding” (Vogue), “smoldering” (The Washington Post) novel by the New York Times bestselling author of...

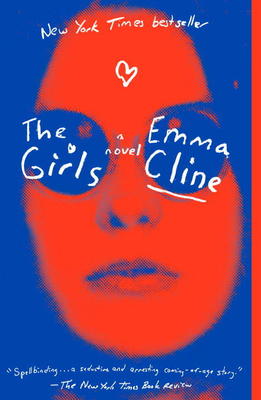

More InfoWhen Emma Cline’s debut novel, The Girls, was published in 2016, it made the kind of stir that any emerging author would be jealous, awed, and, quite likely, frightened of. It was the kind of book that seemed impossible to follow-up, and that was before Cline’s very public legal battle for her intellectual ownership over the novel’s contents. The premise of The Girls was incredibly audacious: a restless, lonely teenage girl swept up into a fictionalized commune-cum-cult over the course of Summer 1969–one of the more famous years for Summer, per Bryan Adams, Charles Manson and Mr. Woodstock of the Woodstock Arts and Music Festival. When The Girls was published, I was still a teenager myself, and completely absorbed by Cline’s controversial, break-neck period-piece and by the immediacy of her teenage protagonist, Evie. Evie was awkward, full of need, and intent on miming maturity to fit in with the hippies, runaways and would-be-murders she was attempting to endear herself to. The novel was full of extremity and simmering, then overt, violence, but what resonated most with me was the complicated and sometimes excruciating humanity of her characters.

The Girls

Emma Cline

THE INSTANT BESTSELLER • An indelible portrait of girls, the women they become, and that moment in life when everything can go horribly wrongONE...

More InfoSeven years after that tremendous debut, Cline’s sophomore novel, The Guest, hit the shelves and received all the scrutiny and attention you’d expect and then some. The Guest’s protagonist, Alex, is twenty-two, and engaged in a performance of the same naivete that Evie goes to such great lengths to conceal. Alex is a maybe-sex-worker, maybe-escort—the novel never describes her work in such specific terms—stranded in the Hamptons at the end of August, trying to kill time before reuniting with her wealthy, older boyfriend. Alex is strategic and simpering in all her interactions, but especially with men. She understands that youth and perceived innocence are tools, to be deployed on those whose sympathies and desires you rely on. Between Cline’s two novels, a pretty bleak but well-trodden gender paradigm emerges, in which girlhood is spent trying to deny and obscure your childness, and womanhood is spent making yourself appear more childlike, more easily exploitable. Alex’s mimed innocence is just that, an act, and one that might grant her temporary protection, but also allows her to manipulate other people’s vulnerabilities to stomach churning effect, including actual children. She is a grown woman who is both forcibly and electively infantilized, making her accountable to no one, including herself.

The Guest is cerebral, taking place almost entirely in the omniscient gap between Alex’s known and unknown motives, in back of her eyelid where a persistent sty keeps forming. It’s interior, but still cinematic and propulsive, like if Paul Schrader had directed Pretty Woman. Alex is artless in her hustling, calculating, but always coming up with the wrong sum. It’s a languid and squirmy read, a bit like waiting to change out of your wet bikini bottoms, conscious that a UTI may be forming, but procrastinating the decision to get back in the pool. I understand that this sounds all-together not super pleasant, but it’s done so artfully that it demands your attention, an infectious read in the truest sense of the word.

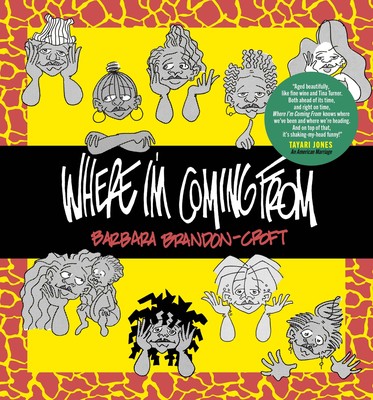

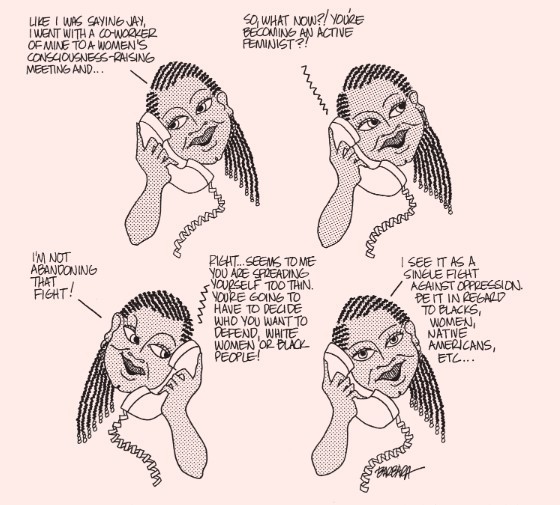

Where I'm Coming From

Barbara Brandon-Croft

A seasoned cartoonist of epic proportions, Brandon-Croft carves out space for Black women’s perspectives in her nationally syndicated stripFew Black cartoonists have entered national...

More InfoWhen Barbara Brandon Croft’s Where I’m Coming From was published in February 2023, it was the first time the brilliant cartoonist, whose work was serialized with the Detroit Free Press in the 90s, was anthologized; the first time her work was given the context, breadth and significance that it has long deserved. Flipping through these pages, Brandon Croft's humour is incisive and uproarious, her commentary on racism, class and misogyny both worryingly and hearteningly prescient. Her work appears alongside ephemera and excellent paratext from the author and her peers that help to situate her voice, politics and distinctive style in context. Where I’m Coming From reads like a fantastic, grownup, Saturday Morning cartoon: brisk, witty vignettes, with an expanding cast of characters glimpsed at through panel, but seeming to share a friendship and rapport that far exceeds the bounds of the frame. Check out my colleague Leïka’s review of Where I'm Coming From to learn more about the phenomenal anthology.

The Pepsi Cola Addict

June-Alison Gibbons

The legendary lost novel in which fourteen-year-old Preston Wildey-King must choose between his all-consuming passion for Pepsi Cola and his love for schoolmate Peggy."He...

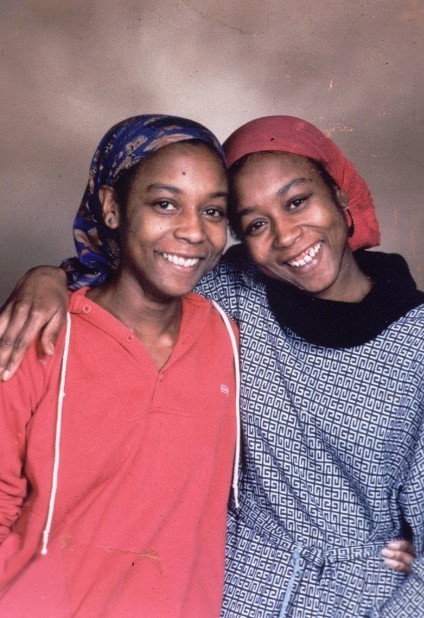

More InfoThe Pepsi-Cola Addict was a highly anticipated read for me, long before I knew if it would even be possible to read it. This republishing from Strange Attractor Press is the first time that this ultimate piece of outsider literature has ever been truly accessible in print. Its initial 1982 run through the vanity press New Horizon resulted in fewer than 10 surviving copies. The author, June-Alison Gibbons, was only 16 when she wrote it. Her and her twin sister Jennifer were precocious, ambitious and intensely inventive writers-collaborators, born to Barbadian parents in Wales in 1963. For several decades, it seemed The Gibson twins would be renowned, not for their life in letters, but as unwitting figures in a wildly misunderstood, sensationalized urban legend. Shortly after The Pepsi-Cola Addict’s publication, the two would become infamous as “The Silent Twins” and cruelly incarcerated for over a decade in Broadmoor psychiatric hospital.

Prior to their institutionalization, The Gibbons sisters were extremely prolific, producing poems, stories, novels, journals and plays to stage with their dolls. The Pepsi-Cola Addict, like most of the sisters’ writing, takes place in America, a place they had never visited but were endlessly fascinated by. They created a painstaking glossary of American terminology and slang, drawn from books, television, movies and pop music, aiming to make the details and atmosphere of their stories as accurate as possible. The alternating precision and anachronism of the world-building of The Pepsi-Cola Addict is part of what makes it such a singular, delightfully strange novel.

The book centres on Preston Wildey-King, a fourteen-year-old boy attending “Malibu High School”. Preston is handsome, broody and listless, dealing with despair, desire and an addiction to Pepsi. The premise is immediately intriguing, but very little was known about the actual contents of the book until its 2023 republishing. When I finally got the chance to read it, I imbibed it in a single afternoon, with all the vigor and speed of Preston downing another 6-pack of Pepsi. June-Alison Gibbons writes scenes of violence and sexuality that are so heightened and surreal that they feel drawn from an intense and profane game of pretend—the ecstatic clack of two plastic Barbie crotches colliding. This, rendered alongside moments that are so startlingly grounded that they catch your breath. Gibbons’ preternatural talent seems both studied and thrillingly unformed, the kind of prose that feels far beyond what a teenager should be able to produce, and also something which only a teenager could produce, full of excess, angst, lust, brutality and queer heartache. When the book is bizarre–and it is truly bizarre–it's bizarre in a way that feels affectively, if not always effectively, true to adolescence. This reprint, created in close collaboration with June-Alison Gibbons, preserves her wonderful idiosyncrasies, honouring her specific teenage voice and specific teenage ambitions. I’ll eagerly read whatever Gibbons chooses to share next, whether it be from her extensive archive or a more recent project. Her teenage voice is so precise and singular that seeing its evolution feels urgently necessary.

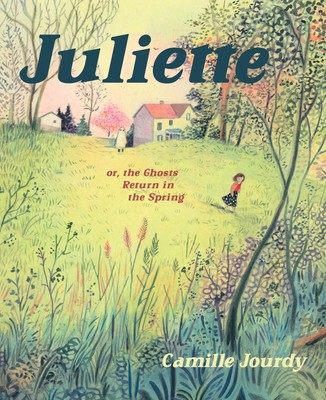

Juliette

Camille Jourdy

A vibrant tableau of small-town life as seen through the eyes of a woman returning home from Paris.Juliette boards a train from Paris and...

More InfoJuliette, or the Ghosts Return in The Spring was among the DQ titles I was most looking forward to this year. The graphic novel is funny and profound, with delicate and intricate watercolour images that demand and sustain your gaze. Author Camille Jourdy creates a story of homecoming, set against the French countryside, that is both exceedingly French and also resonant to those of us with origins as unpicturesque as Southern Ontario. Jourdy’s writing and artwork are all imbued with the unsteady magic of the once familiar. When you return home after a time away, and the places, things and people you recall appear both more and less real than how you’d remembered them. The veil of memory is displaced, like an optometrist clicking a new lens into place inside a phoropter, and the picture you knew as a smudged and fluttering thing coming into startling clarity.