Best of 2022 - Bridget

December 28, 2022

The END of another year! Time marches on. Clobbering us with her sleek leather boots and flattening us under the inevitability of history. This is more or less how it always goes, give or take the 10 days we lost at the swapping of the Julian calendar in 1582. I wonder if there were any enterprising monks doing Best of The Year roundups during the 16th century...

“I cannot recommend highly enough the newest Douay-Rheims translation of Psalms 2 through Maccabees. I can’t wait to read their take on the Old Testament”

“For the history-buff in your life you can’t go wrong with John Leland’s A learned and true assertion of the original, life, actes, and death of the most noble, valiant, and renoumed Prince Arthure, King of great Brittaine”

“The year’s most controversial zine is The Praier and Complaynte of the Ploweman unto Christehe Praier and Complaynte of the Ploweman unto Christe, a polemical pamphlet by an anonymous parishioner that will totally change the way you look at confession, indulgences, purgatory, tithing and celibacy.”

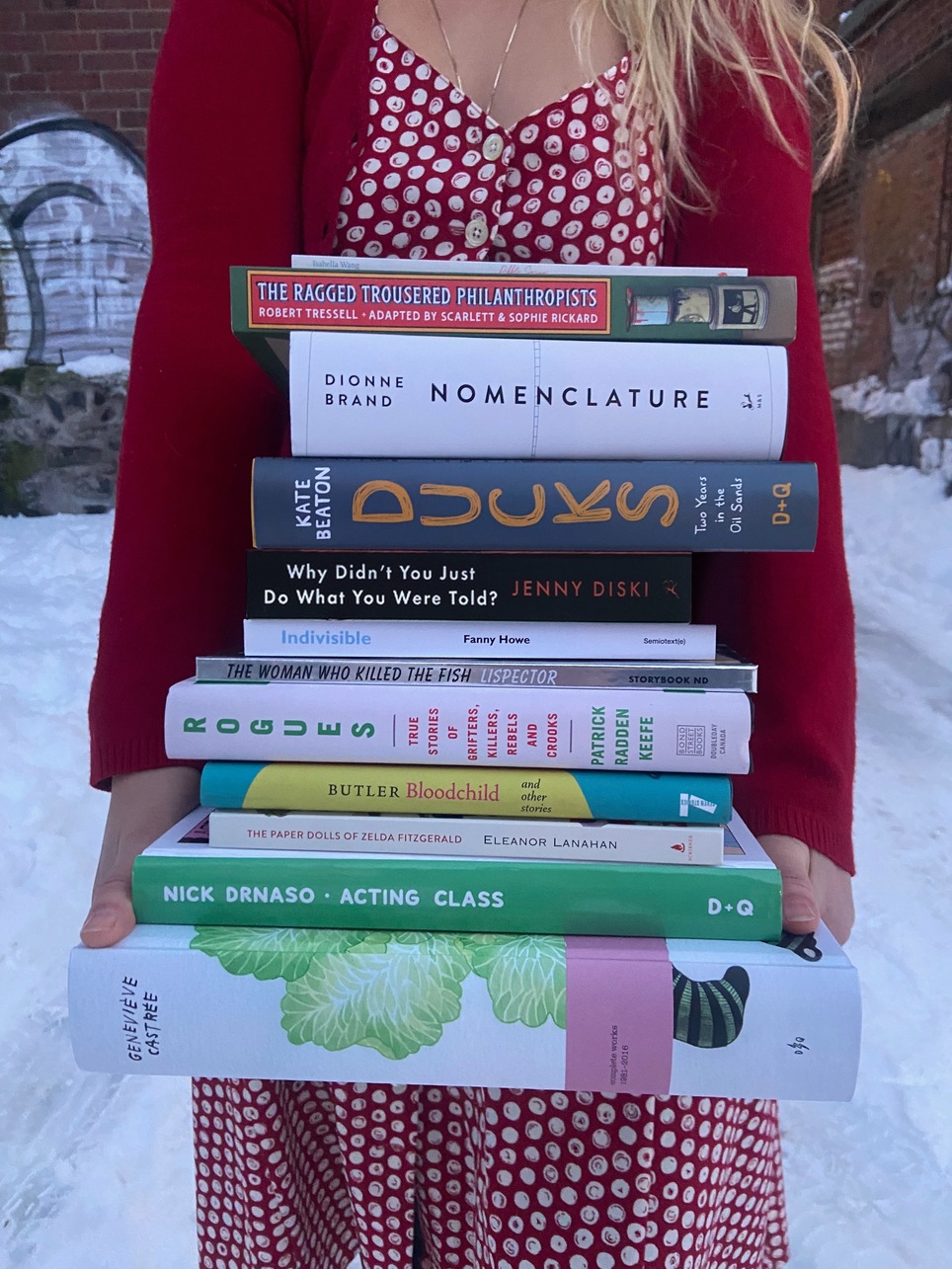

My best of the year, while perhaps less consequential to the protestant reformation, is still chock-full of books that were personally, if not catechistically, paradigm-shifting. Below, you can find a non-exhaustive list of my best reads of 2022.

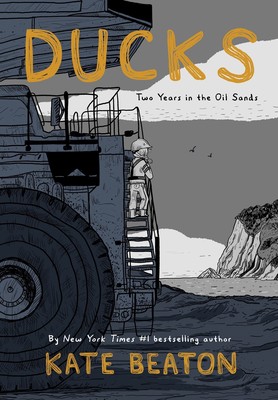

Ducks

Kate Beaton

Celebrated cartoonist Kate Beaton vividly presents the untold story of Canada Before there was Kate Beaton, New York Times bestselling cartoonist of Hark A...

More InfoBeginning with the tar-sands-bildungsroman-as-memoir that everyone is talking about, I will join the chorus of readers that found Kate Beaton’s Ducks to be a revelatory and singular work. It is everything you’ve been told it is: brilliant, beautiful, vivid and soul-excavating. Ducks, along with Jon Claytor’s Take The Long Way Home, which I recommended as part of my summer reads list earlier this year, prompted me to consider how the graphic memoir’s might be able to confound existing narratives about the lands we now call Canada.

Claytor’s memoir took us along with him for a road trip of personal reconciliation, as he sought to make amends and maintain the terrible-twos of his recent sobriety, driving across the wide expanse of highway between the Maritimes and Prince Rupert, BC. Take The Long Way Home renders the scale of something which resists rendering, and is perhaps impossible to even envision, the hyperobject of the nation, forever receding beyond our gaze. It is a story of place and of the self, told in glimpses through the window of a moving car, resistant to the myth of mastery or completeness.

Ducks takes a different approach. In Ducks, Beaton writes about her time in the oil fields of Northern Alberta, at once a tiny, farflung fragment of so-called Canada—one most of us will never see up close—and also, arguably, the locus of our economic and national identity. The tar sands, and the extractivist, world-ending industry they sustain, are routinely disappeared from view. This concealment persists just as they become more and more intractable from the continuance of Canada as both colonial project and a collection of prosperous crude oil conglomerates.

Rather than a zone of proprietary secrecy, Beaton’s vision of the oil fields is a space of exaggerated and outrageous scale, where heavy hauler trucks roam the blackened earth like dinosaurs or some alien species with enormous wheels, and fires blaze from towering oil wells; outsized devastation, outsized debts, outsized egos on puny misogynist men. It's a space of excess and of claustrophic, cramped quarters. The tar sands are a zone where different forms of slow violence accumulate and become all-too-visible, an unexpectedly apt backdrop for the period of personal and artistic transition that Beaton is recalling. It’s a superlative read. It’s also one of the few things former president Barack Obama and I have in common.

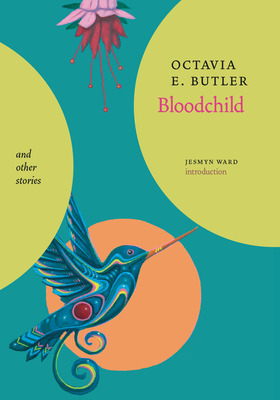

Bloodchild and Other Stories

Octavia E. Butler

A perfect introduction for new readers and a must-have for avid fans, this New York Times Notable Book includes "Bloodchild," winner of both the...

More InfoThis past summer, it seemed as if everyone had joined a secret, exclusive Octavia Butler book club. The store couldn’t get her books in fast enough and couldn’t keep them on the floor long enough to satisfy eager customers clamouring for MORE O.B! I normally wouldn’t begrudge anyone the chance to read the greatest science fiction writer to ever science-fiction-write, but no one would tell me where or when the hell these secret meetings were being held. I roamed around the Mile End like a jerk, clutching my copy of Parable of the Sower, wondering where it was you were all convening.

I suppose the spike in Butler reading could also have just been a collective brainwave to revisit the work of someone who had written so prolifically and brilliantly about the end of the world, especially when our own end of the world is somehow both completely obvious and ridiculous. Seven Stories Press must have tapped into the hive mind, as they have been in the process of publishing beautiful hardcover editions of Butler’s expansive catalogue this past year. Bloodchild and Other Stories is among my favourite works by her, and among the more difficult to find until very recently. It is the only short story collection Butler ever published and a perfect monument not just to her genius, but to the merits of short fiction in general. I love the short story, but I understand this isn't always a popular position! I’d imagine that the shortness of the short-story reveals all too quickly the strengths and snags of a writer’s talents. Like a diorama, the short story doesn’t have the luxury of crafting a whole context to scaffold a narrative, but instead must work in the finicky world of miniatures and forced perspective. All you can access is what is glimpsed through the missing wall, revealing all the writer’s false steps, no matter how subtle.

Butler however, has that rare mixture of talent and restraint that makes her the perfect emissary for the form. Nowhere is this more evident than in the “The Evening and the Morning and the Night”, a story in the collection that assembles its players and its particular dystopia so efficiently and thoroughly that it exceeds the act of reading. It feels both like a world you have long inhabited and one which will continue to startle and fascinate you long after its final page. "The Evening..." is a speculative pandemic narrative that transcends this moment of timely and abundant coronavirus allegories, resisting the very idea of "timeliness". The story articulates more vividly the ableist, capitalist and anti-Black logics that cohere around illness and medicine than any contemporary fictionalizing of COVID-19 I’ve so far seen. It, like much of Bloodchild, offers both a searing portrait of the way-things-are, and a glimpse at the kinds of care that make survivance possible amid that which is unsurvivable.

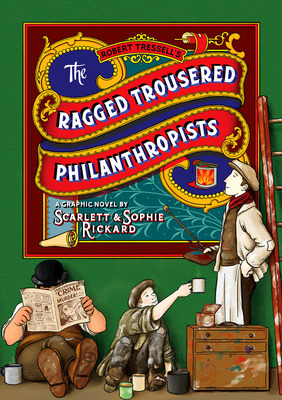

The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists

Scarlett Rickard

A 2022 Eisner Award nominee Adapted from Robert Tressell’s 1914 socialist novel about English working-class life, this British classic sets out the blueprint for...

More InfoThis year, I was delighted to learn about the graphic novels of Sophie and Scarlette Rickard. The Rickard sisters, raised in Ribble Valley, Lancashire, are a couple of years into a very exciting project, the adaptation of literary works which have been foundational to progressive movements historically, but are no longer as widely known or read as they perhaps ought to be.

Last December, the sisters' Eisner nominated adaptation of Robert Tressle’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists was released in North America, making it technically a 2021 publication, but definitely among the highlights of my 2022 reads. The original novel was written over 100 years ago by an Irish house painter, and presents a semi-autobiographically rousing of class consciousness among the workers of the fictional town of Mugsborough. The book has been lauded as essential by the likes of George Orwell (executive producer of the CBS reality competition show Big Brother), but had regrettably passed me by before now. The sisters' collaboration is wonderful and seamless. It makes me almost wistful over the chaos that would ensue if my brothers and I were to make a meal together, let alone a graphic novel. Sophie Rickard does a brilliant job translating and transforming Tressle’s 1914 novel into comic-form, while Scarlett Rickard’s art style feels at once totally her own and also drawn from the rich visual history of labour movements in the United Kingdom and Ireland.

In November of this year, the sisters published their second graphic novel adaption, this time of the 1911 novel No Surrender by Suffragette Constance Maud, which I’m looking forward to reading next. On their website, the sisters write “[No Surrender] is another piece of authentic fiction written by a marginalised person about their experiences. Where The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists is about being poor in a system designed by and for the rich, No Surrender is all about being female in a world designed by and for men.”

Rogues

Patrick Radden Keefe

From the prize-winning, New York Times bestselling author of Say Nothing and Empire of Pain, twelve enthralling stories of misbehavior and skullduggery by one...

More InfoHow can you tell someone in your life is reading a Patrick Radden Keefe book? Oh, we'll tell you alright. His books are full of the kind of details that stick in your mind and appear as irrepressible patter in every conversation you’ll have for the next few months. I get that this may sound annoying, but I promise you my evangelizing is genuine, and has successfully gotten a dozen or so people to read and admire his work for themselves.

Did you hear about the dutch crime-lord who kidnapped the Heineken heir and was ratted out by his baby sister? The scammer-sommelier who faked antique bottles of bordeaux that belonged to Thomas Jefferson, defrauding a Koch brother in the process? Only it isn’t just intriguing premises that Keefe offers, but the insights they reveal about relationships, families, crime and punishment. Keefe attends to the structures which produce the behaviour or people we deem monstrous in a way that feels consistently empathetic, thorough and honest. He resists the reactionary embellishment or outrage that dogs so much reporting on the things we’d rather not think about, in a way that is conspicuously mindful of the porousness that exists at the boundary between “victim” and “perpetrator”. It’s heartening to see his writing ranked highly among bestsellers in the “true crime” category, although the genre feels inexact and almost pejorative when considering the breadth and the carefulness of his work.

Keefe’s 2018 book, Say Nothing, was a phenomenal and thorough oral history of the Troubles, the lives of two sisters imprisoned for their role as militants of the Irish Republican Army, and those “disappeared” during the height of the IRA’s activity. His next book, Empire of Pain, relayed the 100+ year history of the Sackler family as the architects and profiteers of the opioid epidemic. While the continuity between these two projects may not seem obvious at first glance, Keefe does a wonderful job examining the types of violence and general rascality that are permissive and normative, and those that are regarded as deviant. His 2022 book, Rogues, redresses the tenuousness of this distinction in a series of extended essays and character sketches of various “grifters, killers, rebels and crooks”. Each chapter is a distinct and engrossing account of so-called misdeeds and the literal and imaginative retribution we assign them. I have both the hardcover edition of the book and an audiobook purchased through libro.fm, read by Keefe himself.

Acting Class

Nick Drnaso

A brilliant and suspenseful follow-up to the Booker-nominated graphic novel Sabrina. "Every single person has something unique to them which is impossible to re-create,...

More InfoIn the realm of scammers and rascals, I must also offer my ardent recommendation of Nick Drnaso’s Acting Class. The latest graphic novel from the author of Sabrina and Beverly, is equally as disquieting as its older sisters, and just as prescient. The story follows an amateur acting troupe, headed by the incredibly off-putting instructor, John Smith. To say that a current of darkness runs beneath the surface of the class would be to both understate the sinisterness of John’s methods, and to underestimate just how unsettling a normal acting class can be.

Having done theatre and more specifically, improv, for a big chunk of my childhood and early adulthood, the aura of unease, shame and paranoia that Drsnaso renders awakened a kind of acute body-memory between my shoulder blades, even before things started to go truly off the rails for John’s acolytes. Receiving feedback on your ability to embody a role can so easily feel like a referendum on your performance in the role of you. It is a uniquely mortifying and vulnerable position to be in. It is also, regrettably, a thrilling feeling, and a sensation that stands in perfectly for the allure of any cult-like organization.

John encourages his students to begin regarding every gesture, every behaviour as material for theatre, to both study and sublimate themselves in service of a more convincing performance, and to become aware of the strings that are pulled to produce every action and reaction. But the problem with noticing the strings, is that pretty soon everybody around you starts looking like marionettes, autonomous and alienated from any kind of inner world, any mystery that exceeds the act of mimicry.

The release of Acting Class came fortuitously, at the mid way point of Nathan Fielder’s new HBO show, The Rehearsal, specifically episode four, The Fielder Method, which saw Nathan create an acting workshop based around his invented performance philosophy. In several reviews, Acting Class and The Rehearsal were read along side one another, as funny, deadpan explorations of loneliness, fantasy and control. Very much has been written (and very well) on how the two works differ and cohere, but Acting Class roused all kinds of other comparisons for me. Specifically to season 2 of The Vow, a documentary exploring the structure and the fallout of the NXIVM cult and the trial of its leader Keith Raniere. It’s not a coincidence that so many NXIVM members were aspiring actors, despite the organization’s ostensible purpose as a corporate training retreat. In archival footage, we see the cult, then known as an “executive success program” and it is unbelievably wretched in its banality. We see the members play volleyball and have stilted conversations about “ethics”. We see them wander around upstate New York, sing acapella and play some more volleyball. It’s a far cry from the resplendent tackiness of Scientology or the morbid vapourwave aesthetics of Heaven’s Gate. What draws people in, we learn, is something much more frightening and plaintive: some desire to be seen and to be evaluated. To have a charmless, beady-eyed creep like Keith Raniere or John Smith watch your performance of humanity and alternately praise or eviscerate you for it.

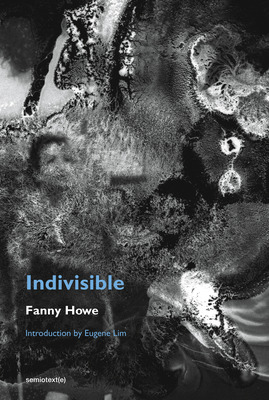

Indivisible, new edition

Fanny Howe

The conclusion of a radically philosophical and personal series of Fanny Howe novels animated by questions of race, spirituality, childhood, transience, resistance, and poverty.First...

More InfoThis year, I finally had the chance to read Fanny’s Howe’s indivisible, a slight, but expansive novel that begins with the homeruner, humdinger of an opening line “I locked my husband in a closet one fine winter morning.” An all-time favourite of my colleague Benjamin, a new edition of the novel was auspiciously released by MIT Press this past April, giving me the perfect opportunity to grab a copy for myself.

I’d read and loved Howe’s poetry before, specifically Night Philosophy and Manimal Wowe, but Indivisible was my first encounter with her prose writing (an irrevocable meeting!), and by far my fastest read of the year. And, not for nothing, but I read almost all of the novel in the waiting room of the Emergency Veterinary Clinic in Lachine. It engrossed me so completely that I almost forgot I was in The Place That God Forgot, perhaps the only genre of building more miserable, more abject, than an ER for humans: an ER for pets.*

The inner world of Henny, the novels’ protagonist and narrator, didn’t just feel like peering inside the world of a vividly rendered character, but sharing a body with her. Howe’s craft is deliberate, delicate and somehow effacing of its own brilliance. Despite the specificity of the world Howe is rendering, a world of artists and activists living and dying in Boston from the 1960s through to the late 90s, the exactness of Henny’s desires and scruples turned me inside out over and over again. Having spent a considerable amount of time in my own company these past couple years, it was a tonic to see some of my most ineffable feelings be… what exactly? effed? by a such a richly talented author.

Henny is an Irish Catholic woman, a foster mum, a filmmaker, and a person well acquainted with the pathos and eros self denial. If there’s one thing, Henny—and by extension, Howe—understand, it’s the art of the pine. And having conducted an informal poll among friends and confused passersby, I think we’re all well quite sick of this yearning business and feel its high time something be done to rectify it. The kind of yearning I mean is so big and so tender that it hates to have its photo taken. Sasquatch-shaped, cryptid desires. What Henny wants, what she pines after, is justice. The kind of justice that is both structural and cellular. Justice that produces an absolute, perfect symmetry; A symmetry of suffering and of pleasure, between the living and the dead, the loved and the unloved, the rich and the poor. To have all our love reciprocated in exact abundance and kind. How we make sense of the impossibility of these desires is a matter of constant rationalization and irrationalization. Henny takes this grievance directly to the source: she takes it up with God.

While reading Indivisible, I was reminded of a wonderful advice column, "Dear Fuck Up", from the tragically defunct Outline. The column, written by Brandy Jensen, concerned a letter-writer who had been suddenly ghosted by her boyfriend of two years (sounds like a good candidate for locking in a coat closet). Jensen, through a brilliant invocation of philosopher Gillian Rose, proposes that there cannot be justice in love, only mercy. This may, at first glance, seem like a pessimistic read on relationships. But it also has a way of exalting the choice to love and to look-after, if we do so with no promise of return or of divine symmetry. Howe, being 82 years old, probably has not been ghosted in quite the same way, but Indivisible is still a book full of small, heartening mercies. Howe doesn't put a stop to the wanting, but commits it to page in a way that feels kind of miraculous.

*For those wondering, the little invalid, Frances (pictured below) made a full recovery. And if Fanny Howe is the man I think she is, her writing likely had a restorative effect on the both of us.

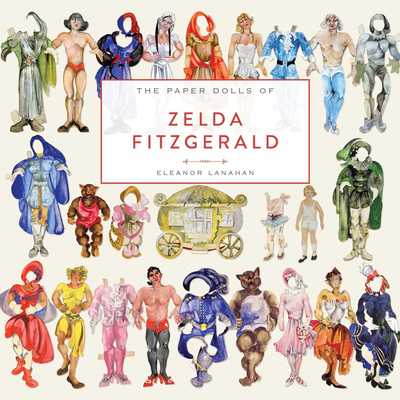

The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald

Eleanor Lanahan

A beautifully designed, full-color collection of paper dolls created by Zelda Fitzgerald, lovingly compiled by her granddaughter, Eleanor Lanahan.Born in Montgomery, Alabama, Zelda Sayre...

More InfoAs a child, one of my prized possessions was the now tragically out of print Fabulous Book of Paper Dolls, illustrated by Julie Collings. The activity book came with dozens of punch-out paper garments, a sheet of adhesive stickers, three paper people and a few cardstock backdrops to pose them in front of. The book’s one flaw was that it was finite. Once the paper people had been punched out and had their paper cowboy boots affixed to their paper feet, they could no longer wear paper sandals or paper slippers. The glue was stronger than it looked and would tear at the dolls or their costumes if meddled with. There were so many possible sartorial combinations to arrange and so few models to style. Knowing how quickly the thrill would pass, I would spend months just looking at the dolls and the clothes, considering all the possibilities that might be foreclosed on once I actually started playing with them.

This is all to say that I was very happy to see The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald be immortalized in this gorgeous new art book, every doll exquisitely dressed but fixed safely and un-punch-out-able to their page. The dolls were all hand painted by Fitzgerald, first as playthings for her daughter Scottie, then as lavish handicrafts. Paper doll making was a lifelong, private pursuit for Fitzgerald. And what results is a wonderful, ornate array of characters, all rendered with evident creativity and care for her subjects: sometimes fairytale characters, sometimes Modernist vanguards, sometimes pure invention. The book, assembled by Fitzgerald’s granddaughter, Eleanor Anne Lanahan, offers a necessary reappraisal of a gendered and maligned art form, and compiles a kind of opulent jewelry box of curios from the Lost Generation.

Nomenclature: New and Collected Poems

Dionne Brand

An immense achievement, comprising a decades-long career—new and collected poetry from one of Canada’s most honoured and significant poets.Spanning almost four decades, Dionne Brand’s...

More InfoI counted down the weeks before Dionne Brand’s Nomenclature arrived in store. And once it arrived, I couldn’t stop fawning over it. It is a massive, stunning collection that spans nearly 40 years of phenomenal writing, from a poet whose skill and influence cannot be overstated.

The first work I ever read of Brand’s was her 2002 memoir Map to The Door of No Return. I say memoir, because that seems expedient and it’s what Penguin Random House would have you believe the book is. But it bears mentioning that Brand’s work continually exceeds its presumptive container, becoming a work of social geography, of poetry, of history, of literary theory and political philosophy. She is a thinker that it would be tempting to call peerless, except that her career is also distinguished by an evidently expansive intellectual generosity and reciprocity, something that has enriched the practice of so many other brilliant Black writers working today in so-called Canada.

This past November, I was able to attend a reading from Kaie Kellough, the massively talented Montreal-based author of Dominoes at the Crossroads and Magnetic Equator. Kellough recalled a conversation he’d had with Brand some years ago, following an academic conference. She’d asked him if he’d been writing poems lately and he had sheepishly confessed no. Brand had emphasized that “poet” was a situation that required active engagement, active creating–a philosophy which may in part explain the impressiveness and prolificness of her output. Kellough recalled feeling daunted but then heartened by Brand’s words. She encouraged him to send her a work in progress and he did.

Kellough’s story reaffirmed my sense that so much phenomenal writing has been buoyed by Brand, either directly or indirectly. You can see the influence of Brand’s vocabularies and lyricism everywhere, once you know to look. Nomenclature begins with a critical introduction by scholar and literary theorist Christina Sharpe, whose 2016 book, In The Wake: On Blackness and Being, is a crucial, virtuosic work that I find myself returning to constantly, and whose forthcoming book, Ordinary Notes, is among my most anticipated reads of 2023. Sharpe’s entire introduction is itself an excellent piece of writing, but I will refrain from quoting more than one paragraph, which attends beautifully to the unique necessity of Brand’s poetic project:

Dionne Brand's poetry makes scalar leaps from the "eroding present" and the "intimacy of history" to "unknown galaxies" and "as yet / unarmed moons," as her work threads multiple temporal worlds- past, present, and futures. With a consciousness that is attuned to this world and open to some other, possibly future, time and place, Brand's ongoing labours of witness and imagination speak directly to where and how we live and also, and necessarily, reach beyond those worlds, their enclosures, and their violences. Brand is, in other words, a poet engagé, and hers is a poetics of liberation; she does not "write toward anything called justice, but against tyranny."

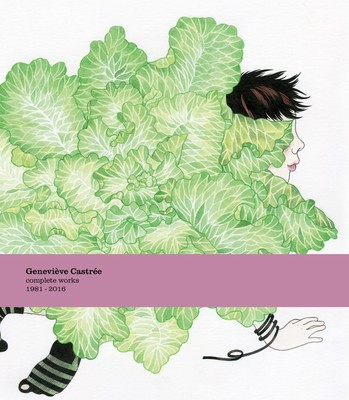

Genevieve Castree

GeneviEve CastrEe

An immersive curation of Geneviève Castrée's stunning life's work and expansive artistic legacy It's not easy to label an artist like Geneviève Castrée—cartoonist, illustrator,...

More InfoThe complete works of Geneviève Castrée is a book so beautiful, you really ought to see and hold it for yourself. The book is beautifully bound and encircled with a pink linen stripe, containing 500-pages of stunning full colour drawings and photographs, designed and curated by Castrée’s widower, Phil Elverum.

Castrée’s art is distinctive and stirring, alternately sparse, then lush, and always evocative of something beyond language. We see some of the same tenderness and calm that filled her 2018 children’s book, A Bubble, and some of the angst and devastation of her 2013 coming-of-age memoir, Susceptible, reprinted in its entirety within the collection. We see the development of Castrée’s singular style and a cache of the beautiful bric-a-brac she amassed and treasured throughout her life.

Only a book of this scope and size could attend to the expansiveness of Castrée’s artistic practice, to the breadth of her work as cartoonist, illustrator, musician, sculptor, stamp collector, activist, correspondent, mother, partner, friend, and so on. It is a book which showcases and engages Castrée’s overwhelming talent, while also being a spectacular work of curation, and curation as an act of love. Elverum’s devotion to the project is palpable and deeply affecting. It is a stunning and fitting tribute for an artist whose passing in 2016 has left an irreparable gap in so many creative communities.

In the interests of not taking up more than my fair share of pixels, I'll leave you with a short list of some other 2022 books I'd recommend checking out. See ya next year!

Short List

Why Didn't You Just Do What You Were Told?

Jenny Diski

A collection of the best of the indomitable Jenny Diski's essays, "one of the great anomalies of contemporary literature" (The New York Times Magazine),...

More Info

Rooms

Sina Queyras

From LAMBDA Literary Award winner Sina Queyras, Rooms offers a peek into the defining spaces a young queer writer moved through as they found...

More Info

Pebble Swing

Isabella Wang

A much-anticipated debut collection from one of Canada’s most promising emerging poets Pebble Swing earns its title from the image of stones skipping their...

More Info

the half-drowned

Trynne Delaney

the half-drowned is a vision of a future at the end of the world where what survives is the shapeshifting love of family both...

More Info

Birds of Maine

Michael DeForge

Take flight to this post-apocalyptic utopia filled with birds. Take flight to this post-apocalyptic utopia filled with birds.Long after the demise of humankind, birds...

More Info

The Woman Who Killed the Fish

Clarice Lispector

“That woman who killed the fish unfortunately is me,” begins the title story, but “if it were my fault, I’d own up to you,...

More Info